Projects in the Field is a series of independently produced articles profiling work supported by NFWF’s Electronic Monitoring & Reporting Grant Program, and is meant to raise awareness and support for these important initiatives. The author welcomes your questions and comments.

In modern natural resource conservation and management we’ve embraced technology to assist us in making the best decisions possible, with long-term sustainability as a principal goal. And while new technology is increasingly accessible, its deployment to monitor and manage fisheries has not progressed at the same pace.

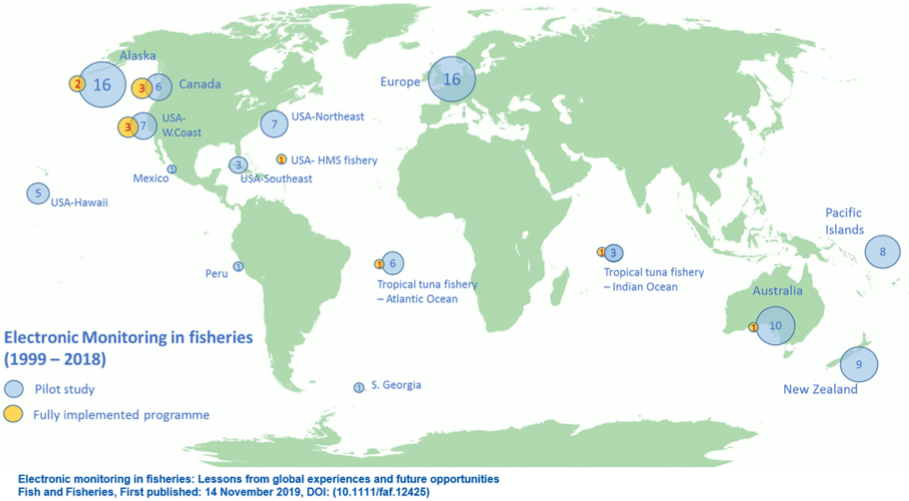

In North America, the first electronic monitoring (EM) trial was in 1999 in British Columbia, Canada, to monitor trap limits and gear theft. In New Zealand, EM was implemented in 2003 to monitor marine mammals and seabirds; and in Europe EM trials started in 2008 (van Helmond, Mortensen, Plet‐Hansen, et al., 2019).

We noticed — just as von Helmond et al documented in their recent publication “Electronic monitoring in fisheries: Lessons from global experiences and future opportunities” — that EM efforts are predominantly absent from regions where small-scale fisheries have a major role (see map above). Yet we know that small-scale fisheries contribute more than half the world’s annual fish harvest (Berkes et al., 2001).

Despite the importance of small-scale fisheries on a local and global scale, they’re largely under-regulated and under-studied in comparison to industrial fisheries (ibid.). Monitoring small-scale fisheries with observers has always been impractical if not impossible, given the size of vessels used, while the costs of human observers are also prohibitive for most small-scale fisheries.

These and other factors contributed to our decision to test EM in partnership with Puerto Rico’s artisanal commercial fishers.

Funded by the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation’s Electronic Monitoring and Reporting grant program, supported by the Ocean Foundation and implemented by Conservación ConCiencia, this project’s objective is to evaluate the potential and efficacy of EM as a monitoring tool in small-scale fisheries, consistent with NOAA Fisheries’ Regional Electronic Technology Implementation Plan for the US Caribbean. Our trials have multiple monitoring objectives including catch monitoring, bycatch monitoring, catch handling, protected species interactions and assessing EM’s use in monitoring for compliance with gear regulations. The project aims to serve as a model for other artisanal fisheries across the US (Alaska, Hawaii, US Virgin Islands, and more) and to encourage them to consider EM efforts of their own.

Over the 24 months of our NFWF grant period (through 2021) our Puerto Rico project will monitor 50-100 fishing trips across 5-10 vessels from the fishing villa (cooperatives) ports of Cataño, Naguabo, Humacao, Guayama, Cabo Rojo, Mayaguez and Rincon.

Commercial fishing vessels in Puerto Rico generally range from 13’-30’ with a few exceptions above and below this range. The vessels used in

our project range from 16’–26’. Gear types include rod and reel, gillnets, vertical and horizontal longlines, bandit lines, traps and scuba gear. All vessels and crew are voluntary participants working under a Marine Conservation Agreement with Conservación ConCiencia.

The EM system used for this project is from Saltwater Inc. It includes a camera and GPS logger with a battery included that connects directly to the vessel’s power supply or to a lightweight, waterproof solar panel. The system is programmed to takes photos continuously at 10-second intervals and for each image to be geo-referenced. Images are saved to a built-in hard-drive in the system. The entire system is contained in a waterproof housing and can be installed and removed with ease on fishing vessels before and after each trip. Because no two vessels in our project are entirely the same, the system is positioned based on gear type, deck configurations, etc. Fishers participating in the project will continuously advise us on optimal camera location for catch documentation.

Saltwater is also providing us with training and support to utilize the review software included with their system, which merges the data collected (location, time, speed and images), to be visualized together at the same time.

As we developed this project we noticed that when we talk about EM, we generally do so in relation to fisheries management, resource conservation and even enforcement. We spend less time exploring direct benefits that EM might provide to fishermen and supply chain participants. In other food industries the organic market has allowed for improved environmental practices in food production. EM can potentially add value to artisanally-harvested seafood products, which in turn could encourage EM uptake in fisheries that are not required to use it. As part of this project we’re going to begin evaluating the potential of EM as a marketing value-add that may incentivize more fishers to use EM. This is just one option; other possibilities like fishing data monetization also need to be further explored and developed.

Most of the world’s established EM programs are in Canada and the United States. Puerto Rico is part of the United States and NOAA plays an active role in managing fisheries here in the US Caribbean (US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico). Considering that the US is already a world leader in EM for larger vessels, we believe it can extend that leadership into EM for small-scale fisheries as well. Of course, EM is not a silver bullet, but we should continue to explore how new technologies can contribute to improved outcomes for artisanal fishers and the health of our marine environment.

As founder and executive director of Conservación ConCiencia, Raimundo Espinoza leads ER and EM projects in the US Caribbean, and currently serves on NOAA’s Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee and Highly Migratory Species Advisory Panel. Rai welcomes your questions or comments at his email here and you can also find him in the Community directory.

References:

– F. Berkes, et al. Managing Small-Scale Fisheries: Alternative Directions and Methods, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada (2001)

– van Helmond ATM, Mortensen, Plet‐Hansen, et al. Electronic monitoring in fisheries: Lessons from global experiences and future opportunities. Fish and Fisheries. 2019;00: 1–28.