Commercial fishing for swordfish in Southern California is experiencing a period of transition, and it is in these periods of flux that opportunities for modernization and innovation can arise and take hold. The recent recommendation for the authorization of a new deep-set fishery for swordfish offers an example of how innovation in fishing gear technology can help provide forward momentum and opportunity during a period of fishery decline. This momentum has segued into the testing of new technologies for other aspects of the fishery, including methods for meeting monitoring and reporting requirements such as electronic monitoring (EM). Considering the health and privacy concerns experienced in 2020-21, the timing was optimal to explore new technologies to meet onboard reporting requirements for the deep-set buoy gear fishery being developed off California.

The Fishery

Commercial fishing for swordfish in California has experienced a slow and continued decline over the past 30 years. Its participants have endured a crippling blend of changing environmental conditions, increased regulation, competition from international markets, and a slew of negative press from various environmental groups.

Because of this decline, there have been fewer and fewer opportunities for local vessels to target swordfish off California. Deep-set buoy gear (DSBG) was developed to address many of these concerns and has been met with enthusiasm by industry, as it is a step towards increasing domestic opportunity. The emerging fishery is a unique symbiosis forged from necessity between fishers and scientists. DSBG is a small-scale hook and line gear type designed by the Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research (PIER), a nonprofit research group based in Oceanside, California. PIER has been involved in each step of the development process, from design and testing to the initial steps towards authorization.

Following fishery implementation, the DSBG fleet is projected to grow considerably as it transitions from exempted status to a fully authorized gear type under the West Coast Fishery Management Plan for Highly Migratory Species. The emerging deep-set fishery has consisted mainly of smaller, owner/operator vessels that use a single crewmember. Because the DSBG design is quite simple, activity on deck is easily observable and quantifiable.

The fishery is currently monitored through human observers, which accompany fishers on selected trips, recording pertinent fishing information and reporting back to governmental agencies in charge of management and oversight.

Why EM?

Fishery observation and monitoring continues to be a mandate of the new DSBG fishery. Currently fishers must coordinate pick-up, boarding, and drop-off for observers at their own expense, steps that can be cumbersome for an artisanal operation. Given the small-scale of the fishery, vessel owners often run at incredibly tight margins and the added burden of these expenses can preclude growth and additional investment back into the fishery. Additionally, inviting a stranger into your home can feel like an invasion of privacy, one that has become less tolerable since Covid entered our lives.

Although we do not see this technology taking the place of observers entirely, for some fishers this could be a very welcome change. For instance, fishers based around the remote seaport of Avalon on Santa Catalina island would not need to pick up and return an observer from the mainland on every observed trip. Similarly, boats with just enough berth space for a captain and his son or daughter could now stay on the fish overnight, instead of having to drop the observer off at the dock at the end of every day. EM could also be used to monitor vessels presently deemed “unobservable” due to working conditions determined to be unsafe for human observers. If EM is proven effective, these represent just a few of the countless scenarios in which electronic monitoring technologies could liberate fishers without sacrificing oversight and accountability.

The Technology

EM is not a particularly new concept as a means of observation, in fact larger and more robust fisheries have been using the technology for over a decade. The challenge in designing an EM system for DSBG vessels was not due to the lack of available systems, but rather in finding a system that could be downsized to provide reasonably affordable coverage for small-scale operations. Features such as artificial intelligence, optical and hydraulic sensors, and multiple camera angles may not be needed for a fishery with a single hauling station and a notably clean catch portfolio. DSBG fishers needed affordable systems incorporating GPS, automation and wireless capabilities, that are easy to set up and service.

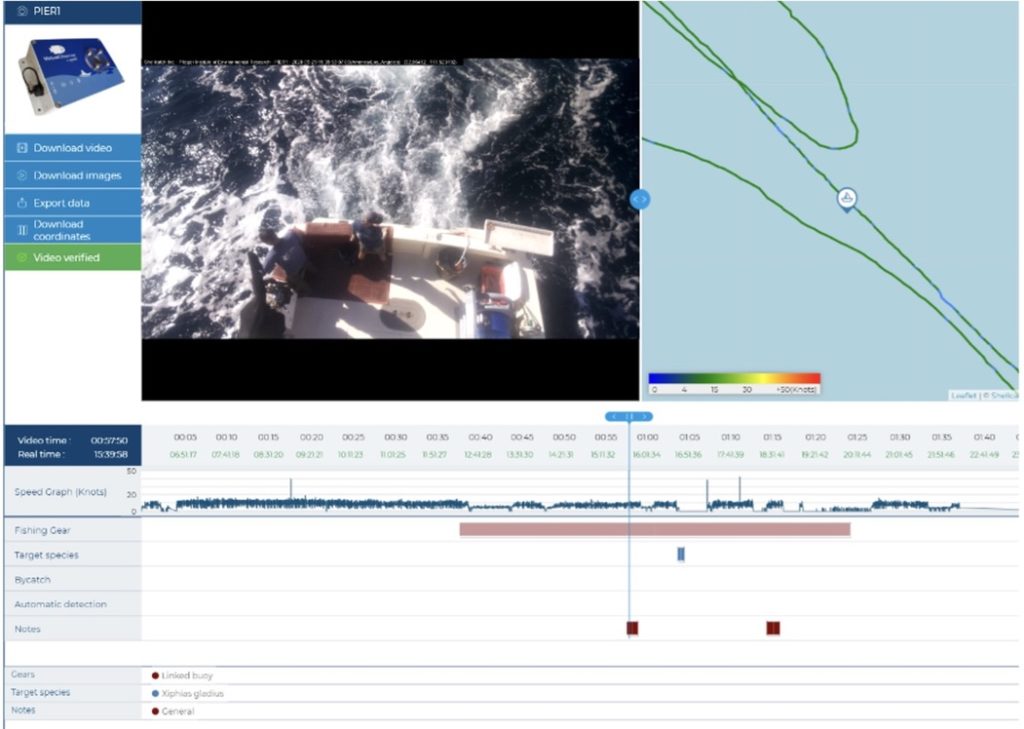

The team offered two separate EM service providers an opportunity to test their preferred “small boat” system in this NFWF-funded project. Saltwater Inc., an observer and EM provider based out of Anchorage Alaska, developed a proprietary two-camera system for the study, while Shellcatch Inc. provided a single camera system that has been used in many fisheries throughout Latin America. The two systems differ slightly in their hardware and technological features, and each has its own respective data processing protocols and review software on the back end. Ultimately, the use of two different systems offers the exploration of a wider range of EM options and increased the scoping capacity of the study.

The Fisher’s Perspective

Initial participants in the DSBG exempted fishery trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of DSBG, while providing sustainably-sourced product that has come to be revered by markets and consumers. Considering the high selectivity of DSBG, with non-marketable bycatch rates below 2% during EFP trials — along with superior swordfish quality — it may be that the role of fishery monitoring could also be used to help promote the DSBG product. Rather than being viewed as a tool for enforcing compliance, a belief that continues to sour relations between fishers and management agencies, it could instead play a greater role in product verification and as a way to justify the premium prices that accompany a superior, “green” product. With the addition of factors such as Covid-19, EM could represent a less invasive monitoring option that also helps fishers sell their catch.

Project Work Plan

With support from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Electronic Monitoring and Reporting Grant Program, PIER designed a two-phased study aimed at testing the efficacy of EM as a means of meeting observation requirements in the DSBG fishery. For the first phase of the project, both camera systems were mounted, side-by-side, on PIER’s research Vessel Malolo as it carried out gear trials and tagging research during the 2020 field season. The Malolo is set up nearly identical to most of the DSBG fleet, offering a perfect platform for the first phase of testing. After working with EM providers to identify and resolve technical issues identified in the testing phase, the team then developed protocols for data handling and review. The next phase of the project was to deploy the technology on three volunteer vessels from the DSBG fleet.

The second phase of the study is currently underway, with both Saltwater Inc. and Shellcatch EM systems actively monitoring three vessels during the 2021-22 season. Data products will be compared with both fisher logbooks as well as concurrent human observation records to verify that camera footage can yield the same metrics generated by physical observers. Although it has taken some time for captains and crews to learn the ins and outs of the new systems, data is currently being collected daily. Meanwhile, video review staff have developed protocols and initiated their review of 2021 fishing activities.

Next Steps

As the team works to compare the EM and observer datasets, both platforms will be evaluated to generate recommendations on system features and to determine if EM provides a viable monitoring solution for the growing fishery moving forward.

Project findings from this study will be used to assess if the existing systems can adequately document DSBG fishing activities, with summarized results published in a scientific manuscript. The work will be shared directly with fishery managers and stakeholders, while highlighting areas where future EM research should focus. Although it may be tempting to claim that technology can solve all our fishery observation problems, this study takes the first step towards identifying viable options that meet the needs of both fishers and managers.

This research was supported by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Electronic Monitoring and Reporting Grant Program and The Nature Conservancy. We are also indebted to the forward thinking fisherman that have made this project possible.

Michael Wang is a field technician at the Pfleger Institute for Environmental Research (PIER), in Oceanside, California. He welcomes your questions or comments. Find more about Michael and PIER in our Community directory. Projects in the Field is a series of independently produced articles profiling work supported by NFWF’s Electronic Monitoring & Reporting Grant Program, and is meant to raise awareness and support for these important initiatives.

# # #