Accurately and promptly estimating recreational fishery catch and effort data is critical for informing effective management of recreationally popular species. However, with an enormous potential “universe” of anglers on the water, the unpredictability of when and where fish will be available, and data lags associated with surveys such as NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP), providing such real-time information has been a persistent obstacle for managers.

Accurately and promptly estimating recreational fishery catch and effort data is critical for informing effective management of recreationally popular species. However, with an enormous potential “universe” of anglers on the water, the unpredictability of when and where fish will be available, and data lags associated with surveys such as NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP), providing such real-time information has been a persistent obstacle for managers.

In recent years, with the proliferation of smartphones, there has been increased interest in developing recreational angler apps to help managers keep a “finger on the pulse” of angler activity and, ideally, to provide a census estimate of total effort and landings. Examples of such apps include Mississippi’s “Tails ‘n Scales” program for red snapper; Alabama’s “Snapper Check” program for red snapper, gray triggerfish, and greater amberjack; and the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s eFin Logbook for golden and blueline tilefish.

To date, numerous studies have explored issues concerning potential sampling biases with these efforts, as well as validation with recreational survey programs such as MRIP. However, while these and other studies have cited angler recruitment and retention as potential barriers to the usefulness of self-reported data, relatively little attention has been paid to examining angler motivations and incentives to participate, and efforts to do so have focused on voluntary self-reporting programs.

The recreational Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery presents a unique case for examining strategies to increase angler self-reporting rates. Bluefin tuna anglers, who must possess a permit for their vessel from the NOAA Fisheries Atlantic Highly Migratory Species (HMS) Management Division, are required to report bluefin tuna landings and dead discards within 24 hours via phone, the HMS website, or the HMS Catch Reporting App. This reporting requirement is intended to provide managers with a real-time estimate to ensure that recreational bluefin tuna landings stay within prescribed limits. This is particularly critical given the unpredictable nature of the fishery, in which bluefin tuna availability to fishermen can change quickly as a result of proximity to shore or weather conditions, leading to large pulses of angling activity. Furthermore, U.S. recreational catch estimates of juvenile bluefin tuna are used to evaluate recruitment in the western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock assessment, underscoring the importance of collecting accurate data from this fishery.

Despite the self-reporting requirement, it is estimated that angler compliance coastwide is quite low, making it challenging for the HMS Management Division to track landings in real-time. Instead, to estimate bluefin tuna harvest the Division must rely on the Large Pelagics Survey, a specialized component of MRIP which operates on a lag of about one month; this impedes managers’ ability to ensure that U.S. bluefin tuna harvest does not exceed its internationally allocated annual quota.

To address this challenge, the American Saltwater Guides Association partnered with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and The Nature Conservancy to conduct a survey of the approximately 2550 private recreational anglers in Massachusetts who possess the permit for their vessel needed to target bluefin tuna, with the goal of identifying concrete steps that NOAA Fisheries can take to improve self-reporting rates. Massachusetts is a hotbed of bluefin tuna fishing activity along the east coast and the diversity of vessels, fishing areas and types, and available fish sizes makes it an appropriate microcosm for the broader angler universe of 16,000 permitted vessels along the fishery’s range from Maine to North Carolina. As a rare-event species with a relatively small angling population, the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery is an excellent test case for examining angler attitudes, barriers, and incentives regarding self-reporting for tracking recreational harvest. The fishery’s low compliance rate underscores the importance of angler buy-in for such programs, even if the reporting requirement is mandatory.

Survey Design and Implementation

Prior to designing the survey, we met with HMS Management Division staff and administrators of other state and regional recreational self-reporting programs along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to discuss key challenges and lessons learned when it comes to increasing reporting compliance among recreational anglers. We were especially interested in hearing about experiences with employment of incentive-based strategies (“carrots”) versus more punitive/enforcement-based approaches (“sticks”).

The survey, which we developed using the online platform Qualtrics, included questions concerning angler bluefin tuna fishing experience and behavior, general attitudes about the fishery and its management, views on the self-reporting requirement, and opinions on the potential effectiveness of certain strategies for increasing self-reporting rates. Before we distributed it to anglers, we reviewed the draft survey with members of the HMS Management Division as well as with Massachusetts bluefin tuna anglers during two virtual focus groups. We also conducted outreach to anglers through social media and an article in On The Water, a popular recreational fishing magazine, to increase awareness and help boost response rates.

One unique aspect of this study was NOAA Fisheries’ provision of data that identified HMS-permitted anglers who had previously self-reported bluefin tuna (“reporters”) as well as those who had never self-reported (“nonreporters”). We sent identical versions of the survey to each of these groups, and were then able to analyze (anonymized) responses based on past reporting history without having to directly ask respondents whether they had self-reported a bluefin tuna in the past. In doing so, we could tease out potential differences between the respondent groups. Unsurprisingly, given the fishery’s low compliance, the survey frame for those who had never reported (n=2417) was far larger than that for those who had self-reported a bluefin tuna in the previous 10 years (n=250).

We distributed the survey in September 2021 through an email containing a link to the survey and a follow-up postcard containing both the survey link and a survey QR code.

Initial Results

While our analysis is ongoing, we’ve already discovered some interesting and surprising results from our survey, which are described below.

Response Rates and Reporting Compliance

Overall, we received nearly 600 responses for a response rate of about 22%, with a significantly higher percentage of reporters responding (about 45%) compared to nonreporters (about 20%). This bias toward reporters is not surprising given that those respondents had by definition self-reported a bluefin tuna harvest or dead discard in the previous 10 years; on average, those folks are likely more aware of and engaged in the bluefin tuna management process, and thus were more likely to respond. Since we largely analyzed responses based on past reporting behavior, however, this bias was unlikely to influence our interpretation of results.

Of the nonreporters who did complete the survey, about 30% indicated that they had harvested a bluefin tuna aboard their permitted vessel in the previous five years—nearly 60% of all survey respondents who said they had recently harvest a bluefin tuna. In other words, based on responses received, we estimated that compliance with the self-reporting requirement in the fishery is only about 40%. However, given the relatively lower response rate of nonreporters, this estimate may be conservatively high. This subset of nonreporters who had harvested a fish but didn’t report it are referred to below as “noncompliers.” Most of our analyses compared responses between reporters and nonreporters and between reporters and noncompliers.

General Views on the Fishery, its Management, and Reporting

With the range of reporting modes—phone, web, or app—available to anglers, we asked which mode respondents would most prefer, and unsurprisingly, the web and app modes were the most commonly selected (each by about 40% of respondents). We did find, however, that those who preferred the phone were significantly older than those who preferred the app or website, and those who preferred the app were significantly younger than those who preferred the website.

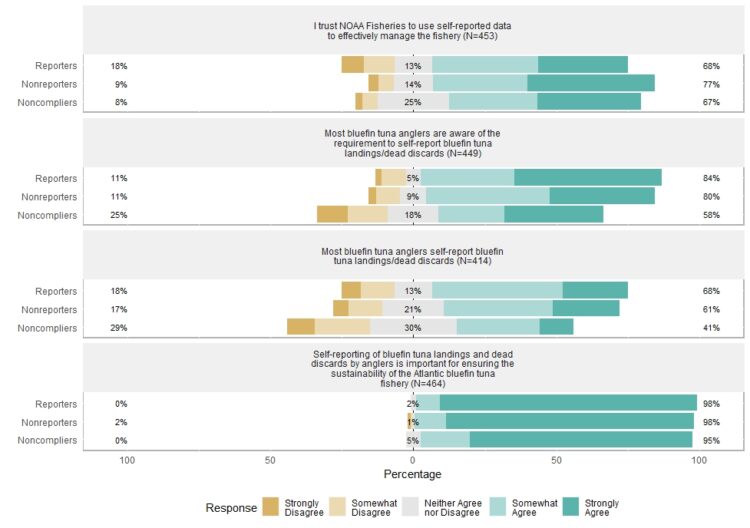

One of the most striking results of our survey was the lack of difference in responses based on self-reporting history. For example, we found that, across all three respondent categories—even noncompliers—over 90% of respondents indicated that they were aware of the need to self-report bluefin tuna landings and dead discards. This result suggests that non-compliance is not necessarily a function of lack of awareness of the reporting requirement, but that other factors are at play. In addition, over three quarters of all respondent types indicated that the HMS website and newsletter were the primary sources of information regarding bluefin tuna management (versus, for example, social media, word of mouth, or online forums).

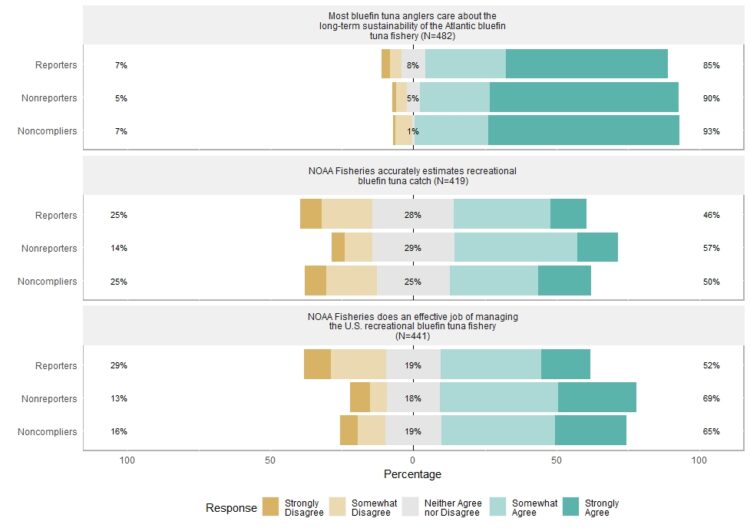

While the vast majority of respondents agreed that anglers care about the fishery’s long-term sustainability, views were more mixed on NOAA’s management of the fishery. Interestingly, over a quarter of reporters somewhat or strongly disagreed with the statement that NOAA effectively managed the fishery—significantly more than nonreporters or noncompliers—raising the possibility that those who were more engaged in in the fishery had less faith in the management process.

There was near-universal agreement, regardless of past behavior, that self-reporting was important for ensuring the fishery’s long-term sustainability. While most respondents agreed that anglers were aware of the need to self-report, a significantly higher percentage of noncompliers—about a quarter—somewhat or strongly disagreed compared to only about 10% of reporters. Similarly, only about 40 percent of noncompliers believed that most anglers self-reported compared to two thirds of reporters.

Again, we found evidence that reporters had less faith in NOAA’s management of the fishery; compared to nonreporters, a significantly higher percentage of reporters disagreed with the statement that they trusted NOAA to use self-reported data to effectively manage the fishery.

Strategies for Increasing Reporting Compliance

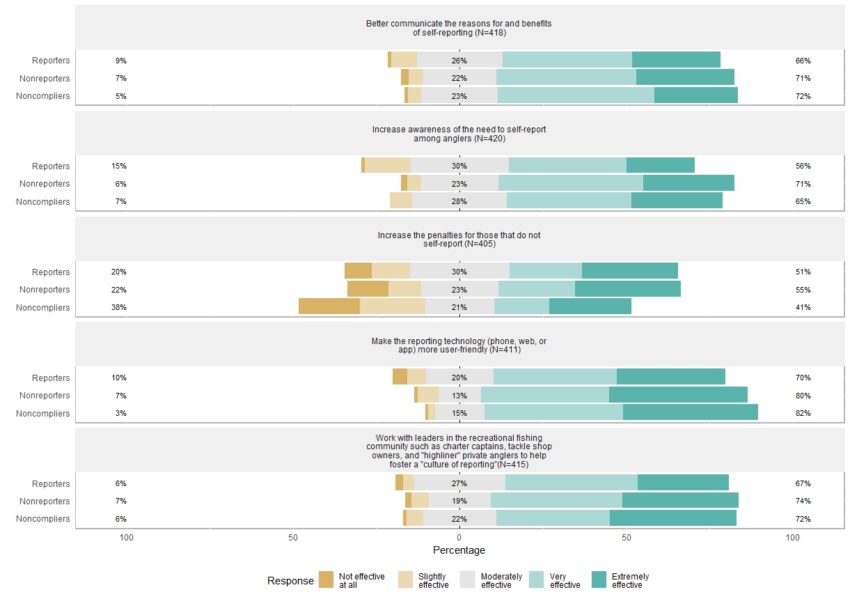

We asked respondents to rate the effectiveness of both general and specific strategies that could be used to increase self-reporting, based on conversations with HMS managers as well as with other state and regional managers who had implemented self-reporting programs. Regardless of past reporting history, respondents generally had positive views of the following strategies: increasing awareness of the reporting requirement; increasing the user-friendliness of reporting technology; better communicating the reasons for/benefits of self-reporting; and working with recreational leaders to foster a culture of reporting. Increasing user-friendliness of the reporting technology—a common refrain heard during our focus groups and scoping discussions—was viewed as very or extremely effective by 80% of respondents. The fact that nearly two thirds of respondents thought increasing awareness of the need to self-report was surprising given the broad agreement that most anglers were aware of the self-reporting requirement. A “stick” rather than “carrot” strategy—increasing the penalties for folks who didn’t self-report—elicited more mixed reviews, especially among noncompliers (nearly 40% of them thought increasing penalties would only be slightly effective or not effective at all, compared to less than 20% of reporters who felt the same).

When it comes to specific strategies that managers could use to increase reporting rates, angler opinions on their effectiveness varied widely by the type of strategy.

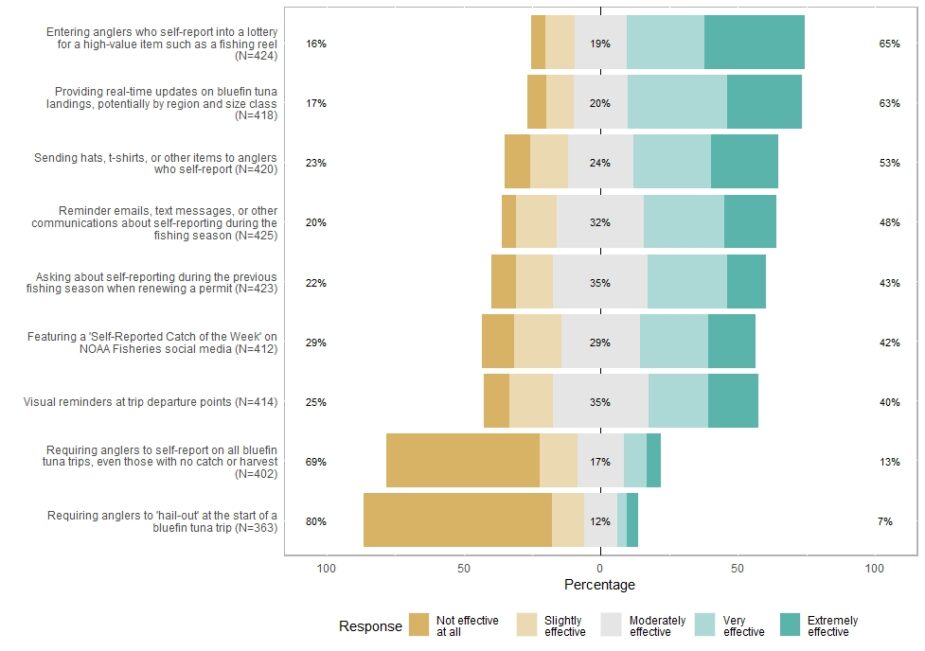

Incentives were certainly the most popular means for increasing compliance. The strategy most broadly viewed as effective was entering anglers who self-report into a low-odds, high-value lottery for an item such as a fishing reel; nearly two-thirds of respondents, regardless of past reporting history, believed it would be very or extremely effective, a significantly higher percentage than any of the other strategies listed. While a lottery has the potential to increase reporting, it could also lead to “perverse incentives” for overreporting if the “prize” is too valuable, so managers would have to be careful in designing such a program and perhaps find ways to verify catch.

The strategies viewed as second- and third-most effective for increasing response rates were also incentive based: 1) providing real-time updates on self-reported bluefin tuna landings over the course of a season; and 2) sending small items such as hats or t-shirts (“swag”) to those who self-reported. Perhaps unsurprisingly, those who had already reported in the past were less enthusiastic about real-time updates, possibly out of concern that such an incentive could lead to more crowded conditions on the water.

Strategies that served the purpose of reminding anglers of the need to self-report, such as reminder emails, visual cues at trip departure sites, or asking about reporting during the previous season when renewing a permit, were generally viewed as moderately effective. Those who had previously reported, however, were less enthusiastic about the idea of asking about self-reporting from the previous fishing season when renewing a permit—only about a quarter thought it would be very or extremely effective compared to nonreporters. This result could be because if reporters were already complying, they likely wouldn’t be interested in assuming more of burden as part of the process.

The strategies viewed as least effective were those that imposed an additional burden on anglers through requiring them to either 1) self-report on all trips, including those with no catch/harvest; or 2) “hail-out” at the start of a trip. For both of these options, over 50% of respondents thought they would not be effective at all.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps

Overall, our survey revealed that, while there is broad awareness of the self-reporting requirement among Massachusetts recreational bluefin tuna anglers, compliance with that requirement continues to be low—only about 40%, according to our results. There was, however, interest in incentive-based approaches for increasing self-reporting rates. In addition, there may be opportunities for NOAA Fisheries to improve its reporting technology and conduct outreach and communications approaches to ensure that anglers understand the self-reporting requirement and the benefits to both the resource and the fishery that could result from doing so. Such outreach could be beneficial not only to compel nonreporters to report harvest but to ensure that reporters continue to do so given that that group demonstrated less confidence in NOAA Fisheries’ ability to use self-reported data to effectively manage the fishery.

While this project focused on Massachusetts bluefin tuna angler electronic self-reporting, our hope is that its findings can help inform efforts to increase compliance at a fishery-wide scale and can readily be transferred to other recreational fisheries that rely on self-reporting to support effective management.

Willy Goldsmith is Executive Director of the American Saltwater Guides Association. If you have questions about this project he is happy to hear from you at willy@saltwaterguidesassociation.org. Projects in the Field is a series of independently produced articles profiling work supported by NFWF’s Electronic Monitoring & Reporting Grant Program, and is meant to raise awareness and support for these important initiatives.