Across Northeast Asia, Ocean Outcomes is facilitating the uptake of new technologies such as electronic monitoring to support better fisheries management and improve fishing practices.

Taiwan represents a significant proportion of the world’s distant water fleet, harvesting highly valuable commercial fish such as tuna that are vital to global food systems. However, these fisheries are plagued with critical issues: they operate with fewer than 5% onboard observer or electronic monitoring coverage, relying heavily on potentially biased self reporting. Moreover, bycatch and interactions with Endangered Threatened and Protected (ETP) species persist as serious concerns. This situation fosters an environment where many vessel operators engage in Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing practices, including underreporting catches, shark finning, retention of ETP species. Tragically, labor and human rights abuse also stain these operations. The lack of accurate and timely fisheries data undermines effective management by regulatory bodies, hindering their ability to make informed decisions. This not only jeopardizes the sustainability of fish stocks, but also threatens the livelihoods of those dependent on these resources. Furthermore, these gaps create a spill-over effect into markets, perpetuating IUU activities globally.

To address these key pillars of sustainable fisheries management, fishery managers and market leaders are looking towards electronic monitoring as a cost-effective solution to expand the availability and accuracy of fisheries data. Electronic monitoring has shown promise in reducing bycatch, improving compliance, and supporting crew welfare. Despite growing interest in advancing electronic monitoring, progress has been hindered by flag states and fishery managers’ ability to incorporate it into a national policy and regulatory framework with sufficient capacity for managing electronic monitoring systems — an underlying factor for enabling electronic monitoring to scale in countries like Taiwan.

In the upcoming years, Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMO) members are expected to further focus their efforts to date on ensuring the effective implementation of electronic monitoring programs with the goal of gradually achieving 100% coverage of industrial fisheries to meet full transparency and accountability necessary to combat IUU fishing.

Furthermore, in response to ongoing threats to ocean ecosystems, including accidental catch of non-targeted species, illegal fishing, and abandonment of fishing gear, retailers have announced more robust sourcing requirements to ensure transparency and data gathering in the tuna supply chain. These requirements, applicable to Walmart U.S., Walmart Canada, and Sam’s Club suppliers, mandate that tuna suppliers exclusively source from vessels with 100% observer monitoring by 2027 and from fisheries using zero high seas transshipment unless covered by 100% observer monitoring by the same year. These announcements are further driving the need for the adoption of electronic monitoring to meet international market demands.

Through a growing partnership with Fue Shin Fishery Ltd (FSF), and the National Taiwan Ocean University and Fisheries Agency of Taiwan, Ocean Outcomes is helping to install electronic monitoring equipment and implementing its supporting technology on distant-water longline tuna vessels. These trials are supporting two goals: (1) assisting vessels involved in Fishery Improvement Projects in gathering independent catch data, and (2) accelerating local capacity for electronic monitoring development.

This work is part of two Fishery Improvement Projects between Ocean Outcomes and FSF. These projects have mandates to enhance the transparency of fishing operations, generate and provide better fisheries data to managers, and increase observer coverage. While the ultimate goal of these projects is to support FSF in achieving Marine Stewardship Council Certification, FSF recognizes the importance of supporting the long-term viability of the tuna stocks on which they depend.

Already some shipowners and captains who are part of the work are starting to see the upsides to electronic monitoring — better data, easier compliance with international standards, market and brand recognition. However, some have mixed feelings about the technology and its costs, privacy implications and potential complications associated with technological advances. To address these concerns, the pilots associated with this work include hands-on training to crew members on use, maintenance and repair of electronic monitoring systems. While collaborative pilots develop at the vessel level, project stakeholders are working to support Taiwan in developing a comprehensive regulatory framework for electronic monitoring to standardize the technology and its use across the entire fleet. These pilots are the first step in the journey ahead to increase transparency in Taiwanese distant water tuna fleets which are among some of the highest risk fisheries in the world.

Over the past year, this initiative has installed electronic monitoring equipment across four Taiwanese vessels with a plan to add another eight by the end of 2024. The below images and their captions highlight how this collaborative work is advancing electronic monitoring in Taiwanese tuna fisheries.

Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) — which oversee tuna fisheries — are gradually increasing monitoring requirements. They are also calling for increased coverage and minimum observer percentages across various gear types, as well as establishing standards for electronic monitoring systems and electronic reporting. These increased standards for improving transparency and data gathering are also being called for by seafood buyers, such as Walmart which recently announced a new policy asking tuna suppliers to 1) “Source exclusively from vessels that have 100% observer monitoring (electronic monitoring or human observer)1 by 2027; and 2) Source from fisheries using zero high seas transshipment unless the transshipment activity is covered by 100% observer monitoring (electronic monitoring or human coverage)2 by 2027.”

Observers are independent specialists who serve on board commercial fishing vessels. They monitor and collect data on where a vessel is fishing, the type of gear used, the fishing activities occurring, catch composition, and interactions with marine mammals, sea turtles, seabirds, and other protected species. This data is used to inform fishing and fisheries management at the government and RFMO levels.

Monitoring fisheries is challenging, especially when distant water vessels operate far from shore for very long periods of time. Simply put, there are not enough observers to cover all the vessels that need monitoring. Further, the observers themselves are also required to work long hours, face a variety of occupational hazards, have personal safety concerns, and cannot provide 100% observation over the duration of a fishing trip given a vessel’s working hours.

Electronic monitoring offers an opportunity to address RFMO requirements, market requirements and many of the challenges related to onboard observers. For example, electronic monitoring can increase observer coverage at lower costs (over time); increase transparency and data integrity; and contribute to more sustainable fisheries management measures.

Taiwan currently lacks a comprehensive electronic monitoring policy and regulatory framework, however, which has significant implications for the management and oversight of its fisheries. Without such a framework, it is difficult to standardize, mandate and implement the technology across its fleet. Across Taiwan, observer coverage hovers around five percent, far below the levels necessary to ensure effective monitoring and sustainable practices.

Electronic monitoring trials to improve observer coverage take place in Donggang, where one of Taiwan’s largest fishing harbors is located. While at port, vessels which are part of the project have received new electronic monitoring equipment and training on its use.

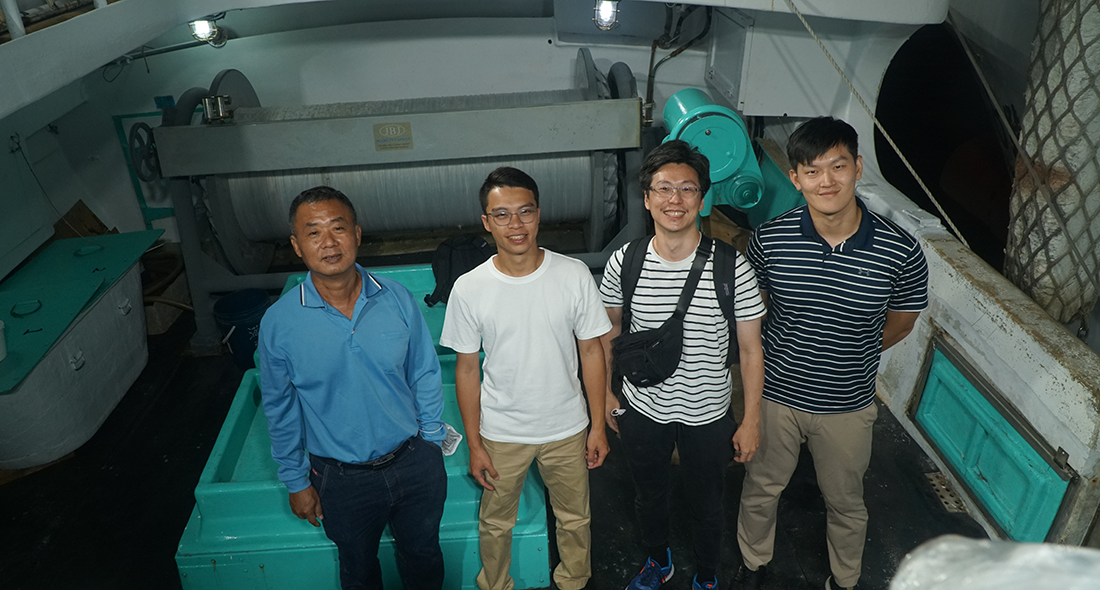

Wen-Sheng Chen (pictured left), is a ship owner who had new equipment installed on his vessel. Although not all owners and captains are enthusiastic about the new technology, Chen is supportive: “Putting these systems on my boat helps us stay on the right side of the rules and boosts our standing in the global market. It’s a tough change, but it’s something we need for the future.” This work was completed with support from the project team in Taiwan — Ming Jhang Chen formerly with the fishing company FSF, William Hsu of the National Taiwan Ocean University, and Ho-Tu Chiang of Ocean Outcomes.

So far, the team has installed electronic monitoring equipment across four vessels and plans to do another eight this year. This work is all part of two Fishery Improvement Projects led by Ocean Outcomes and FSF which are working to improve social responsibility and environmental sustainability on participating Taiwanese longline tuna fishing vessels.

As we support the implementation of electronic monitoring systems in Taiwan’s tuna industry, this technology will bring significant benefits. It will enhance transparency, ensure compliance with international standards, and ultimately contribute to the sustainability and profitability of our fisheries. This is a crucial step towards a more responsible and forward-thinking approach to marine resource management.

Ho-Tu Chiang is Asia Fishery Improvement Manager and Jeremy Crawford is Asia Fisheries Director for Ocean Outcomes.

![]()